Artists: Jean-Claude Mézières

Jean-Claude Mézières

Where do ideas come from? Question every writer hates. “Oh, they just float in the air above and sometimes I’m quick enough to grab one.” But really. Who came up with the concept of time and who was the first to imagine the future? Somebody, somewhere came up with the notion of gods. Creatures, concepts, contraptions and ideas of what is possible within the limits of ones imagination.

Then someone else attempted to visualize those ideas. Perhaps even more vividly than the words, these visual representations have entered the collective consciousness. From Hieronymus Bosch’s ‘Garden of Earthly Delights’ and Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel paintings to the illustrations in the early Hugo Gernsback Science Fiction magazines, these images have codified the unseen possibilities into concrete visions, which have then steered the whole of humanity on its path. Sometimes for the good, sometimes for the bad, yet where but in caves would we be now if it weren’t for the dreamers?

Then someone else attempted to visualize those ideas. Perhaps even more vividly than the words, these visual representations have entered the collective consciousness. From Hieronymus Bosch’s ‘Garden of Earthly Delights’ and Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel paintings to the illustrations in the early Hugo Gernsback Science Fiction magazines, these images have codified the unseen possibilities into concrete visions, which have then steered the whole of humanity on its path. Sometimes for the good, sometimes for the bad, yet where but in caves would we be now if it weren’t for the dreamers?

There is a lineage of these visions and dreams, hard to trace, but somewhere along that brush line sits comfortably the work of the artist-dreamer Jean-Claude Mézières.

Mézières is best — and almost exclusively — known for co-creating with his childhood friend Pierre Christin the long-running series featuring spatio-temporal agents Valerian and Laureline. What began as a short adventure strip in 1967 has spanned the following 50 years with a continuous output of over 20 adventures in what is possibly the most influential and entertaining science fiction comic book series ever published.

The Valerian and Laureline titles are among the best-selling titles in the history of French comic books. They have been translated to and published in over a dozen languages. Drawing inspiration from classic pulp science fiction, and enhancing that material with serious commentary on socio-political issues — like colonialism, racism and imperialism — these adventurous entertainments manage a harmonious balancing act between the two sides. Any ten year old kid, boy or girl, can rapturously enjoy the tales on a level of sheer adventure. Valerian is an athletic agent with quick reflexes and the ability to engage almost any situation head-on, while Laureline is the brains of the operation, equally adept and capable, but with a bit more of both sense and sensibility. Through these characters and their interaction with a wide variety of fantastic situations, the stories educate and entertain with subtle persistence and keen observation.

The Valerian and Laureline titles are among the best-selling titles in the history of French comic books. They have been translated to and published in over a dozen languages. Drawing inspiration from classic pulp science fiction, and enhancing that material with serious commentary on socio-political issues — like colonialism, racism and imperialism — these adventurous entertainments manage a harmonious balancing act between the two sides. Any ten year old kid, boy or girl, can rapturously enjoy the tales on a level of sheer adventure. Valerian is an athletic agent with quick reflexes and the ability to engage almost any situation head-on, while Laureline is the brains of the operation, equally adept and capable, but with a bit more of both sense and sensibility. Through these characters and their interaction with a wide variety of fantastic situations, the stories educate and entertain with subtle persistence and keen observation.

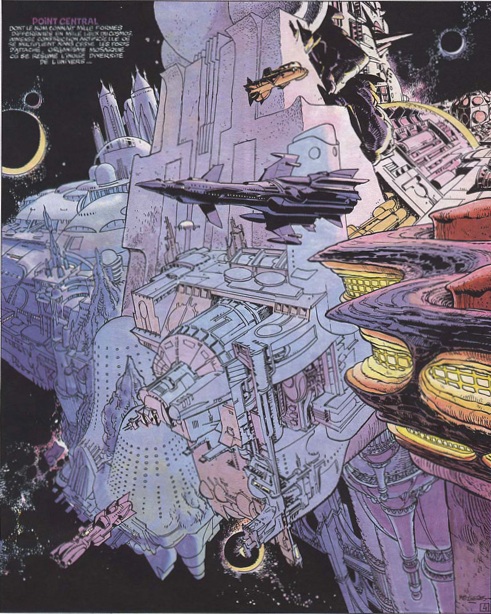

Mézières’ evocative work has the pure essence of cartooning. His lines are striking but modest, holding a complexity that rarely demands attention instead of inviting it. Mézières’ work actually undercuts his mastery of composition by using such a gently humorous approach to his characters. When illustrating some of the grandeur of the universe he can be methodical and precise, but his creatures — human or alien — are drawn with loose, organic lines. This constant interaction between the scenery and the characters creates a contrast that grounds the stories in reality, but allows for them to be universally accessible, alive and entertaining. Will Eisner compared his work to that of Winsor McCay for “its towering knowledge of perspective and the solidity of construction.”

As masterful the work in itself is — and this is a series that took a few episodes to start truly firing on all of its cylinders — what has solidified Mézières’ status in the annals of the art is something rarely acknowledged. His influence towards the visuals of the science fiction cinema.

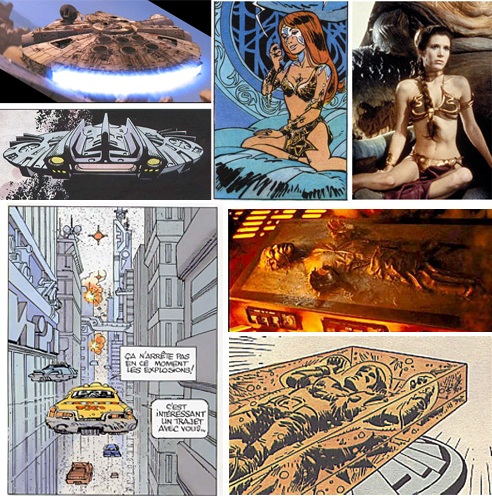

It is interesting to note many of the similarities between Mézières’ work and the imagery of George Lucas’ Star Wars films. One could perhaps ignore the likeness between the Millennium Falcon and the spaceship Mézières came up with a decade earlier, but when you compare the brass-plated garments Carrie Fisher wore while in Jabba the Hutt’s lair with a strikingly similar dress worn by Laureline back in 1971, or place some of the aliens in the Mos Eisley cantina sequence next to those in Mézières’ work, a pattern emerges. What was credited to Lucas’ imagination now can be seen under a different light. You can take a look at many other blockbuster films and their design, and note unusual similarities. Some spectacular work for which Mézières was properly credited for is to be found in Luc Besson’s Fifth Element. Bruce Willis would not be a cab driver racing in that teeming metropolis if Besson hadn’t read The Circles of Power, published at the time Besson was preparing for the film. And Besson, of course, finally took that early inspiration and released his Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets in 2017.

It is interesting to note many of the similarities between Mézières’ work and the imagery of George Lucas’ Star Wars films. One could perhaps ignore the likeness between the Millennium Falcon and the spaceship Mézières came up with a decade earlier, but when you compare the brass-plated garments Carrie Fisher wore while in Jabba the Hutt’s lair with a strikingly similar dress worn by Laureline back in 1971, or place some of the aliens in the Mos Eisley cantina sequence next to those in Mézières’ work, a pattern emerges. What was credited to Lucas’ imagination now can be seen under a different light. You can take a look at many other blockbuster films and their design, and note unusual similarities. Some spectacular work for which Mézières was properly credited for is to be found in Luc Besson’s Fifth Element. Bruce Willis would not be a cab driver racing in that teeming metropolis if Besson hadn’t read The Circles of Power, published at the time Besson was preparing for the film. And Besson, of course, finally took that early inspiration and released his Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets in 2017.

So whether acknowledged or not, Jean-Claude Mézières is one of the great living visionaries. He is superbly influential and universally respected. He won the Grand Prix at the Angoulême International Comics Festival in 1984 for his body of work, joining the ranks with legends like Moebius and Will Eisner. His co-creation is one of the greatest science fiction entertainments ever published. His work remains timeless, and the universality of issues discussed within the stories makes even the early works of the Mézières – Christin duo vivid and engrossing today, over half a century later.

I am also happy to note that this intelligent, intricate but exuberant work is finally being published in full, in the English language by Cinebook, in affordable but handsome editions. The first title, The City of Shifting Waters, was published in 2010, and the publication of all the books is nearly complete. I most enthusiastically recommend the support of this series and its publisher.